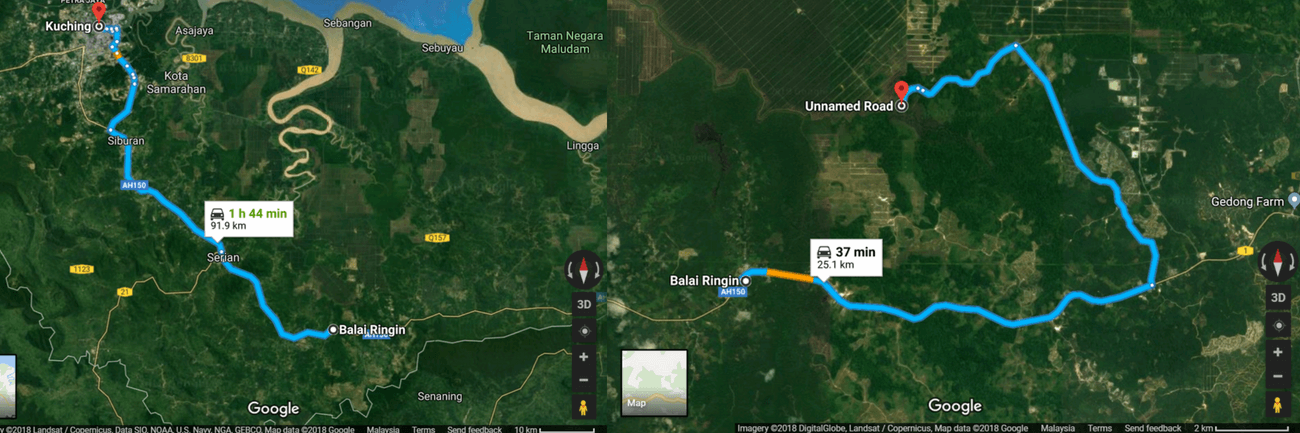

Semada Belatok is a village of about 200 people, mainly composed of Ibanese natives. Located in Serian division, it is approximately one-hour away from the nearest town, Balai Ringin. To get there, we turned off the main road into an unmarked side road that wound past a quarry, sporadic patches of pepper farms, and oil palm plantations. The tar road abruptly ended and we continued on a teeth-chattering gravel road for another 30 minutes, before thankfully connecting back to a narrow strip of asphalt as we approached the village.

The journey going into the village actually took close to an hour because of the road condition.

A Recent Plight Brought On By Changing Landscape

39% of rural populace in Sarawak still does not have access to clean water, especially in the coastal area and the state’s central zone (Source).

When Lily’s (53) ancestors first settled here, they relied on the river and rainwater harvesting for their water supply. More than 60 years later, they still rely on natural sources, but much has changed.

Around ten years ago, the land around the village was cleared for planting oil palm. Gradually, the quality of the river water deteriorated; it became muddier and the villagers were wary of using it, afraid that chemical pesticide may have contaminated the water. They had no way of knowing at that time, but a far deadlier threat awaited in their waters.

“My wife was sick and hospitalised in Serian so I was harvesting the paddy on my own that day. I finished work late and headed to the river to bathe. As I was cleaning myself, I felt a sharp pain on the side of my body. I thought one of the village kids must have thrown a rock at me as a prank but when I turned around to look, I came face to face with a crocodile. My blood ran cold. It had the right side of my body down to my knee in its jaws. The croc’s snout brushed against my skin and it felt like ice,” recounted Alang. The attack happened in 2009.

“I don’t know where I found the will to move, but I punched the croc with all my strength. Luckily, I hit its eyes and it released me. I count my blessings everyday that I survived but if it was a child, he or she would not have stood a chance.”

When the land was cleared for oil palm, the developers dug waterways throughout the plantation. The crocodiles use these waterways as a shortcut to reach the village, creating a danger that never existed before.

In 2016, it was reported that the crocodile population had grown to 12,000 in 45 rivers in the state. The Sarawak Forestry Department also reported that up to 27 people have been killed in 52 crocodile attacks since 2010 (Source).

Now that the villagers’ movements and activities in the river are limited, their main water source shifted to rainwater. However, with a growing population and unpredictable periods of drought, it is not enough to sustain the village’s needs.

“We use rainwater for everything; drinking, cooking, washing, bathing. It’s not enough, we still have to buy cartons of drinking water from town. Still, we’re very careful with how we use water. We reuse and recycle water; bathwater and laundry water can be used to flush toilets. Even now I have a full tank of rainwater but I worry whether it’ll last us through this dry season,” says Lily.

Rainwater harvesting system; each house has a similar set-up with an average of four tanks per house.

In times like these, the villagers have no choice but to draw water from ponds that they have dug themselves. The water here is muddy and smells grassy, and is used for bathing only.

Each family had to spend money to dig a pond and buy a pump to transport water to their homes in times of drought.

“You can see for yourselves, the water looks like Milo (chocolate drink). The soap doesn’t lather when we use this water and there’s a slimy feeling,” explained Peter, a relative of Lily. This is what the people of Semada Belatok have come to accept as a way of life, as they are left with no other option.

Leader Continues to Safeguard Her Community’s Welfare

Lily was the first person we met in Semada Belatok. She holds the title of tuai (village head) and is the first female to do so in her village. Despite having only visited her on two occasions, her hospitality and warmth made us feel very welcome. A natural born leader, she has a “tell it like it is” straightforward attitude and easy confidence that makes her widely respected and liked by the community.

Lily Ak Gunggang; daughter, mother, wife, and leader. She may have many roles but she manages well and has a positive energy.

Besides being the first female tuai, Lily is also the first to be elected to the post. Conventionally, the tuai is selected by the District Office (DO) through a nomination and interview process. This time around, the village decided that they wanted to choose their tuai themselves as was their tradition.

“When I first started, I felt nervous and a little bit scared. It was all so new to me,” says Lily. “I didn’t know if I was going to get the community’s cooperation. I’m one of a handful of women leaders in a male-dominated environment, who would listen to me? Thankfully, I have my community’s full understanding and support. I find it much easier now and I have a strong sense of purpose.”

Now, four years into her tenure, Lily continues to safeguard her community’s welfare, as the previous tuai, Tagong, who is also her uncle, has done. Tagong held the post of tuai for 31 years, he took over from his aging father at the behest of the villagers and the district officers. “Back then, I rowed a boat all the way to Balai Ringin for meetings and official business,” he told us, a nostalgic smile played on his lips. Photos of him with government officials and the certificates he had accumulated over the years were framed up on the wall.

More importantly, his contributions to the village can be seen everywhere we look. He worked to get a road connecting their village to Telagus and managed to get it partially tarred. In the early days before they were connected to the power grid, he applied for a power generator from the DO, which he personally transported in his boat and set-up with help from villagers.

He requested for a community hall for the villagers to hold activities and celebrations and it was also during his time that he implemented a ‘Healthy Village’ programme with the help of the Samarahan Health Department, where smoking was prohibited within homes. Those who wanted to light up can only do so at designated huts throughout the village. The programme saw a significant decrease in smokers.

One of the smoking huts in the village. With the decrease of smokers, these huts are usually occupied by villagers chatting and enjoying the evening scenery.

Tagong has done a lot for the village and he was ready to step down and spend the rest of his days resting and caring for his grandchildren. One thing that still weighs heavy on his heart is not being able to solve the water issue for his village. He had applied for a survey to be done by the Department of Mineral and Geoscience, but the results show no feasible groundwater reserve in their immediate vicinity.

“My village is beautiful, we love it here. My wish is just for us to have clean water, to not have to worry about the dry season, to not have to fall sick because of drinking dirty water. Please help my village,” pled Tagong.

Tagong and his wife, Remi.

His sentiments are shared by everyone in the village, especially Lily, who is now responsible for her community. We will be working closely with Lily and the people of Semada Belatok to come up with a solution for the water quality and scarcity issues here. Lily is optimistic and hopeful for what the future may bring once the water issues are less pressing.

“I have an idea to start a homestay here. The view in our village is beautiful and I think other people would think so too. I want to share our culture and our way of life.” Lily excitedly described all the activities and games she had planned from boat rides to traditional dances. Her energy was contagious and we got excited for her too.

“I think this would really be good for my village not only by helping us earn a little bit more income, but also to bring us closer together as a community and as a family. I really look forward to it.”

The Ibanese community of Semada Belatok.

A Community Project Beyond Basic Needs

Our community project in Sarawak kick-started early this year, and is made possible by our sponsor, YTL Power for Social Outcome Fund in partnership with Agensi Inovasi Malaysia (AIM). We will be engaging with the communities in Kampung Semada Belatok and Kampung Sion to uplift and empower them through community peacebuilding training, and working together to come up with sustainable solutions to their basic needs issues.

Written by

Yong Joy Anne, Storyteller